Artist Biography

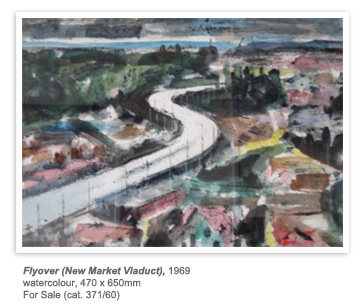

Nevertheless his work undergoes considerable change between his early studies of the 1950s and his late acrylics of the 1980s. From an essentially drawn, often monochromatic approach, he evolved to a more highly coloured and painterly style. At no time was Thompson affiliated with a particular group of New Zealand painters. Yet, because he was based throughout all his working career at or near Auckland he was in touch with the main developments in contemporary New Zealand painting. He exhibited frequently with the Auckland Society of Arts of which he was a member, though in later years he preferred to show at private dealer galleries, such as John Leech Gallery, New Vision and Gallery Pacific. His painting was occasionally reproduced, for example in the Year Book of the Arts, but was to attract relatively little critical attention.

There comes quickly a sense that Nelson Thompson was in many respects a modern or neo-romantic painter. In this he reveals the strong debt to English art in his visual background and training. The revival of a romantic mood in British painting of the 1940s and 1950s provides a necessary framework for his beginnings as an artist. It also provides the basis for the degree of interpretation and choice of subjects, especially in his paintings of the 1950s.

Thompson preferred to sketch from specific subjects, often drawing them on the spot in a series of studies. From these he would develop the larger, finished versions at a later date. Even so, much of his painting is small in scale, domestic rather than public in aspiration. Frequently he favoured pen and ink, or watercolour rather than oils as a medium. Consequently there was a close match between his technique and the modest actual size of his imagery. In his scale of working Nelson Thompson has affinities with English painters of the 1930s and 1940s like Paul Nash or, one might add, the expatriate New Zealander Frances Hodgkins. In this his work fits comfortably into the context of Auckland painting of the 1940s and 1950s. Even the early abstract paintings of Milan Mrkusich remained small until the 1960s.

In his later works, Thompson felt little need to enlarge the physical size of his painting to any great extent. Rather, in his later paintings, the imagery is larger in relation to the format resulting in an increased feeling of breadth, matched by a more gestural execution. In these works he achieves a freedom in his nature studies which is more abstract and comparable with the related imagery of Gretchen Albrecht and Pat Hanly of that time.

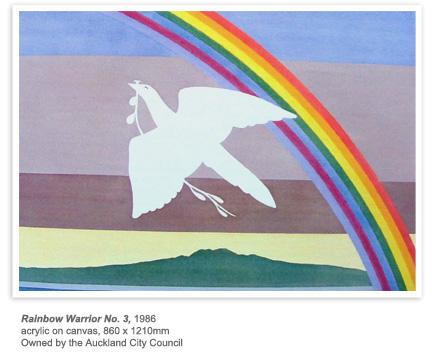

Interestingly, although there is a powerful landscape emphasis in Thompson's art, he cannot be called a regionalist. True, most of his subjects are New Zealand ones, but he does not focus upon national icons, or subjects chosen for their characteristic national features. Instead, it seems that nature in general rather than particularity is his main concern. The sense of place emerges without self-conscious emphasis, and is the more effective for that fact. Only very late in his career, notably in the Rainbow Warrior paintings does any overt political message appear in his art. But there is always an underlying concern for nature, conservation and harmony between the individual and the environment.

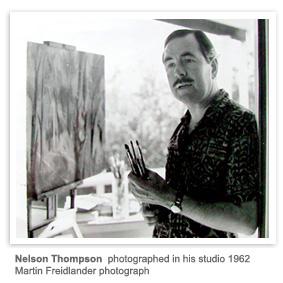

His painting is not an isolated development either locally or in terms of British post-war painting. His years in London and time at the Chelsea School of Art had an enduring impact on his development as an artist and enabled him to have first-hand contact with the work of Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, Paul Nash and John Piper, among others. He developed there his love of fine draughtsmanship which was deepened by a study of Old Master drawings at the British Museum. On his return to New Zealand he began to adapt what he had seen and learnt to local subjects and conditions.

In finding through his Rainbow Warrior Painting No. 3 an articulation for his feelings of social concern and protest Thompson was taking a direction found increasingly in New Zealand painting of the 1980s. Instead of standing back from issues, artists like Pat Hanly and Ralph Hotere, to name a few, saw painting as a means of consciousness raising above social and political issues. Characteristically Thompson here was not abrasive but conciliatory, finding in nature images of calm and order. This seems in retrospect to be an appropriate note with which to conclude his career as a painter. The works have a message of peace for the living and of hope for the dead. The dove is in flight, passing from the terrestrial sphere to the celestial suggesting a spiritual journey - the passage to souls after death to the next world.

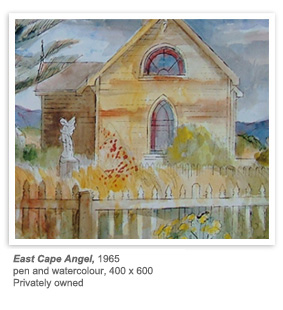

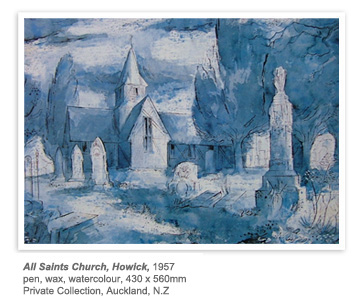

British Neo-Romanticism preferred subjects with a history, where the present was seen as overlaid by the past - a quality Piper found in the works of Samuel Palmer, an artist deeply admired by Thompson. In Piper's favoured architectural subjects, the topographical aspects are outweighed by sentiment and nostalgia. By dramatic chiaroscuro, by emphasis on decay, mystery, and melancholy mood Piper loads his works with Neo-Romantic emotion. This kind of presentation, along with the architectural subject-matter, is relevant to some of Nelson Thompson's best works of the 1950s.

One group of works where such ideas emerge is of colonial churches. Thompson found in the Gothic Revival forms of Auckland's Selwyn churches the right kind of subject and associations for his Neo-Romantic interests. Here he was able to combine, as had Piper, the architectural forms with an evocative, landscape environment of dark trees, neglected grounds, threatening skies and dramatic lighting. Of these paintings, All Saints Church, Howick 1956, St Stephens Judges Bay (cat. 2/50) plus St. Johns College Chapel (cat. 76/50) are an important example. Like Piper, Thompson has drawn All Saints with pen lines which define architectural forms like the transept and tower. But this is not an orthodox architectural drawing any more than are Piper's related works. Instead, his broad use of blue/grey wash to create patches of deep shadow plunges part of the church into darkness and helps to merge it with the gloomy cypress trees and gravestone shadows. In addition Thompson has picked out areas of the spire, tower and gable in white body-colour, as he has some of the grave-stones, not in a logical fashion but with a feeling for mood and sentiment. By employing restricted colouring he transforms the image from a comforting scene to one that conjures up thoughts of death, of history, of those who have lived and worshipped here and who have now passed away without trace - except for these fragile remains. This reflective, melancholic mood is characteristic of Neo-Romantic art, especially when combined, as here, with the associations of Christianity, the spiritual and the Gothic.

In New Zealand painting the colonial church and graveyard were visited by a number of artists influenced by British Neo-Romanticism. But the drawn dimension of Thompson's painting, as well as his use of watercolour, bring to mind more the works of Eric Lee-Johnson than the large oils of Sutton. Thompson would have been familiar with Lee-Johnson's watercolours at the Auckland Society of Arts exhibitions. Clearly Thompson and Lee-Johnson shared much the same sources in British art which both had studied at first hand in London.

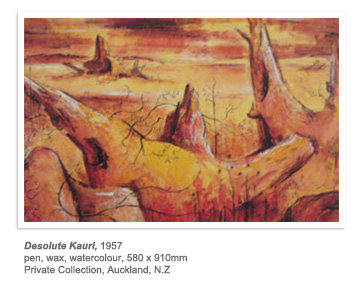

In Desolate Kauri Thompson has intensified the mood of his painting by bringing the main forms up close to the viewer so that we look past them to the empty expanse beyond in an accelerated perspectival diminution. This pictorial device was used often by the Surrealists, notably Yves Tanguy, and here helps Thompson to give the scene a greater sense of tragedy by magnifying the scale of destruction. His colouration, yellow ochre and red, can be seen symbolically to bring to mind the fire of the burn off and the writhing flame-like forms are a metaphor for the instrument of their destruction. Thompson's technique requires the use of pen lines to shape and animate the forms with movement in some kind of slow, death struggle. The mood Thompson achieves is the melancholic one of silent reflection.

Henry Moore observed: 'A large piece of stone or wood placed almost anywhere at random in a field, orchard or garden immediately looks right and inspiring.' This observation helps to explain another part of the attraction dead tree forms had for Thompson and the Neo-Romantics. The found object provided a ready-made work of art filled with animistic and associative potential for subjective interpretation.

This helps explain a painting like Pohutukawa Stump 1961 (cat. 280/60). The Moore-like appearance is apparent despite its New Zealand origin. Isolated, made prominent and 'placed' in a landscape this stump is like a natural carving with its varied curves, protrusions and hollows. Seemingly the artist needs only the eye to find and record the form with all its potential meaning. Thompson's vision here, as in the preceding examples, retains its British as well as its local dimension. Also, it was the associative mobility of works like Lee-Johnson's The Face in the Cliff 1946 (Artist) where the viewer can read the image, according to associative response, as anthropomorphic. In both Thompson and Lee-Johnson there are some relations with English Surrealism in the allowance for interpretation in which the subconscious has a part to play.

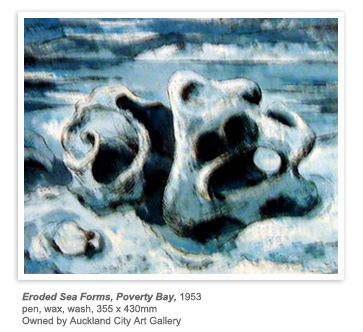

This applies equally to works like Eroded Sea Forms, Poverty Bay 1953 (cat. 56/50) a type of subject also prominent in the watercolours of Lee-Johnson. As in Pohutukawa Stump, Thompson has selected the forms found in nature because of its animated, life-like quality. The forces of wind and tide have, like the sculptor's chisel, hollowed parts of the surfaces, abraded others, and in places totally perforated them. By giving the forms a grandeur of scale and a strong range of chiaroscuro, Thompson creates the 'inspiring' natural artwork admired by Moore and associated British artists. It suggests age, decay, the forces of time and the inevitable mortality of all things.

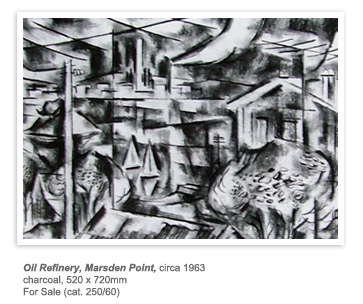

Other subjects which have similar qualities are old boats and tackle, as in The Meat Lighters, Gisborne 1958 (cat. 65/50) or Gisborne Harbour Board Yard 1954 (cat. 116/50). In these images the works of man are shown mouldering away in fields where grass and weeds begin to soften and break down the artefacts of industry. Machinery, too, has its life cycle, and, once outmoded and disused can be accommodated to the Neo-Romantic taste. Comparable decaying farm implements and old agricultural machinery are found in Frances Hodgkins' paintings of the 1930s.

Only when mechanical creations are disused and put on the scrap-heap do they allow the appropriate reflections on the inevitable decay of all material things - a reflection melancholic in mood and so sympathetic to the Neo-Romantic imagination. In such subjects. Nelson Thompson's sensitive, irregular line-work and broken, textured colour found full scope for expression.

Nelson Thompson in adapting the Neo-Romantic style to New Zealand subjects, gave them a greater sense of history and meaning. It is precisely this kind of enhancement that lies behind the popular landscape works of contemporary photographers like Robin Morrison. Painters like Thompson helped to shape the way contemporary New Zealanders see their country and its heritage

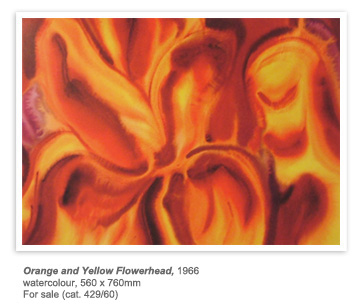

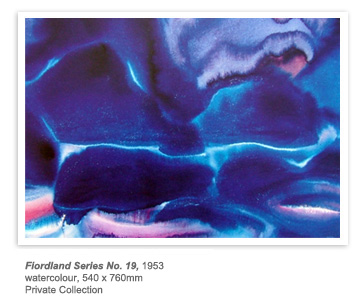

In Gopas' imagery, as in Thompson's, colour is pitched beyond the intensity of realism and is guided more by feeling than concern with naturalism. The landscape becomes a motif for the painter to interpret more or less freely. The clearest indication of Nelson Thompson's new-found interest in Expressionism comes in his watercolours of flowers and flower-heads dating to the late 1960s, and the Fiordland and Earth and Sky series of the 1970s. In these works there is an obvious debt to the watercolour landscapes and flower paintings of Emil Nolde. Writing in 1986 Thompson recalled: 'Fortuitously I discovered the work of Emil Nolde, the German Expressionist, whose brilliant brushwork of flowers and landscapes on wet paper are among the finest in the watercolour medium. Here was a path to follow and so I evolved a technique of painting directly with a brush without any preliminary drawing onto paper thoroughly saturated with water.

Writing of this procedure in 1986 Thompson noted: 'For subject matter 1 chose flowers and plant forms from my own garden. Carefully drawn tinted studies were translated into direct paintings where the botanical facts disappeared in favour of controlled shapes in a range of personal colour choices. The end results were paintings of multiple shapes and colours unrecognisable botanically but having a life of their own.' Thompson had a long-standing enthusiasm for gardens and had made more literal studies of plants and flowers in drawings of the 1950s, and early 1960s. But his new paintings transcend those in scale and confidence.

Orange and Yellow Flower-Head circa 1965 (cat. 429/60) is a good example of these new watercolours. Thompson painted this and many related works such as Purple Flower Centre circa 1968 (cat. 432/60) on sheets of Fabriano paper - a heavy paper able to take a soaking in water. After soaking the paper in a bath of cold water he could float the colour on in layered washes. An essential part of this approach is its directness - for the artist must be skilled with the use of wet on wet washes. Of this process Thompson wrote: 'I found that this method called for a highly developed technical facility for as the paper dried out each succeeding wash of colour reacted in a different way. There was a precise moment when one wash could be applied to best advantage. This wet technique called for precision and decisiveness to keep a fresh and spontaneous look to the finished work. The pen had been eliminated and was now used solely for drawing.'

In these paintings Thompson magnifies the flower-heads, blurs them, and fills the whole foreground expanse of the picture surface. The shallowness of spatial depth and the way the patterns of the flower-heads spread across the paper give a more abstract, less natural compositional emphasis. The Flower-Head paintings are more abstract than his earlier Neo-Romantic works and more modernist in their approach to a shallow surface composition. This awareness of surface pattern and abstract formal values is very apparent in both Orange and Yellow Flower-Head (cat. 429/60) and Purple Flower Centre (cat. 432/60). It is also noteworthy here that Thompson is working in a series of related images which collectively add up to more than the content of any one work. This, too, is typical of much modernist painting and shows his changed approach to picture making.

His landscapes of comparable technique, like Earth and Sky No. 5 circa 1968 (cat. 394/60) allow washes of rich colour to flow across and down the paper suggesting, in their variation of size and hue, the shape of clouds, of light breaking through, of rain falling and of sky and water meeting. These works are open, free of any human inhabitants and human handiwork. They have the generality and abstraction now central to this phase of Thompson's art. As with the flower paintings, in these landscapes he is much more surface conscious than in his earlier works. The veils of colour flow across and down the paper, they are not drawn to a line or edge, but seem to expand outwards. It is as if the total image has been cropped and that we see a part rather than the whole. This is a quality found in much abstraction of the late 1960s; for instance in the works of Helen Frankenthaler, an American painter whose work Thompson admired. Like Frankenthaler, Thompson for a time used acrylic paints on unprimed canvas enabling him to carry through his watercolour methods in a medium more congenial to him than oils.

After 1976 he evolved a series of landscapes arranged across the surface in bands, with alternating tones of light and dark to suggest horizons. In 1986 he said that these works: 'developed into the Earth, Water, Sky series where I used elements of the visible world such as tidal estuaries, hills, clouds and sky under changing conditions of light and atmosphere.' An example of these paintings is Earth, Water, Sky Horizon series No. 15. (cat. 502/70).

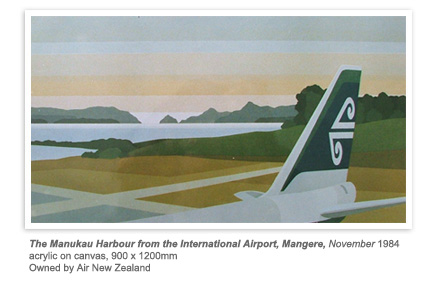

re-assess his approach to painting and return to a more descriptive style of landscape. In these works like Cape Wiwiti, Bay of Islands circa 1983 he re-introduced foregrounds and backgrounds, and precise profiles of landforms. In this example, Thompson uses the acrylic medium on primed canvas to give a more solid feel to the colours. It is noticeable in this painting that one of his main concerns is with the patterns made by the water, mudflats and coastline. He has coded each of these to a specific colour and tone so that the landscape takes on a sharp, clear, almost decorative aspect. The result is pleasing and accessible. Perhaps it is not surprising that similar works were among Nelson Thompson's most commercial successes. His procedure with these paintings involved preliminary studies made on the spot, plus some use of photography.

Among the artist's later works are the larger Rangitoto Mural cica 1985 and the Rainbow Warrior series circa 1986. In these he combines his sharp, patterned treatment of landscape forms with symbolic images of peace and hope - the dove and the rainbow. In this work, unusual because of its clear reference to a specific political incident, Thompson achieves a synthesis of elements that had potential for further development. In his last unfinished painting of Mangawhai Heads he projected the juxtaposition of hard edge coastal images with flower-head shapes suggesting a way his work may have evolved. The Rainbow Warrior paintings have a message of hope and peace. The dove is in flight, passing from the terrestrial sphere to the celestial, suggesting a spiritual journey - the passage of souls after death to the next world.

© Michael Dunn

(A PDF copy of the original retrospective will soon be made available - please refer to the enquiries page)